Vietnam

Sapa

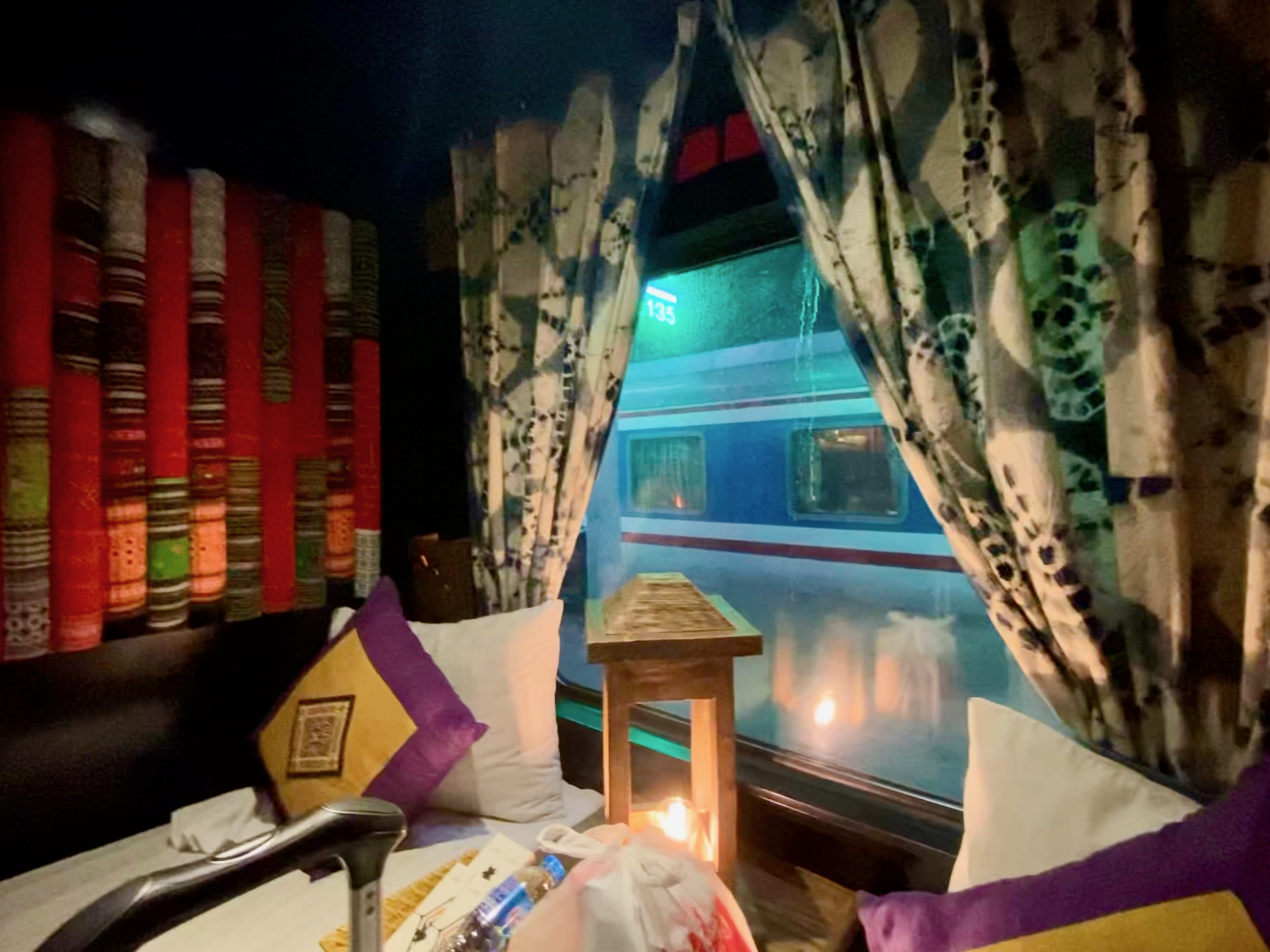

Sleeper Train to Sapa

I write to you from the sleeper train from Hanoi to Lao Cai. The journey from the capital will take eight hours, from 10pm – 6am. The destination is Vietnam’s border with China. From there we will take a car about an hour to Sapa, and then do a two-day trek with local guides from the Hmong hill tribe through rice fields and mountainous countryside, including a night over at a local homestay with mosquito nets and the whole nine yards.

This all sounds like some legit adventuring if you’ve never been to Hanoi.

If you have been to Hanoi, you know this is the bread and butter, ultra-touristy, most basic thing you can do here. It’s one part of the three “must-do” excursion trifecta from Hanoi, the other two being boating around Halong Bay and tromping around Ninh Binh. Around us on the train are old people decked in full Old People Traveling Uniforms: expensive REI capris, breathable tops, technical socks, and hiking shoes.

We sprung for the luxury sleeper cabin which has just two beds instead of four, a probably futile attempt to score as many of the possible eight hours of sleep by avoiding reported shenanigans like people coming in and out of your room, either with a proper ticket from a later stop or just attempting to find a nicer seat.

After settling in, someone came by and gave us sweetened welcome tea, potato chips, some good looking bananas, and the second-worst wine I have ever drunk in my life. And I have drunk some bad wine. No cockroaches yet and the wifi actually works. I am a big fan.

A couple things I’d add after-the-fact:

-

I agonized over the best way to get to Sapa. There’s no perfect option. The alternative is a 5.5 hour bus, which either eats up a day or guarantees a sleep-deprived night. Even though a two-person train cabin was much more expensive, given the general confusion of trains01 and what it’d be like with two strangers sleeping in the same cabin,02 I think it was worth it, for us.

-

That said, if I was to go a second time, I’d take a bus. The train is a novelty experience. The unending creakiness and sideways motion really transports you back to an era of vintage trains and quickly de-romanticizes them.

The shuttle from Lao Cai to Sapa was packed with cheery Singaporeans who had field trip energy about them, then promptly started vomiting on the curvy drive up the mountains.

Plus many many many many twists and turns.

Sapa

I started to be wary when we got to Sapa. The town has the creepiness of a place that not only 100% caters to tourists, but was built to do so. In other words, you can feel the recent explosion in development. Can see it still happening. Nothing seems to exist that isn’t in service of adventure seekers coming to trek.

Aside from restaurants, hotels, and trekking services, the weirdest part of town was a central and perpetually sparse plaza.

I can’t remember if the electronic billboard was broken, but I think it’s just the photo.

We got some eggs and industrial-strength Vietnamese coffee before starting the quest.

These drip-by-drip apparatuses make pour overs seem like an express process. They produced bean juice approximately the quality of jet fuel. But it was hard not to get addicted to coffee with sweetened condensed milk dumpd in.

Trekking

Trekking is the word given to Sapa’s Officially Mandated Tourist Activity (OMTA). You get a guide and walk around the villages for one to three days. The locals are an indigenous people called the Hmong.

Both friends-of-friends who had gone recommended a company called Sapa Sisters. We hired a guide for two days. The itinerary: walk among the villages; your guide prepares food in their home; overnight homestay in a village; trek back.

We were groggy from the train, but optimistic. After the glowing review from my old friends,03 we were excited for a challenging but growing experience. Plus, we felt like we were supporting a good cause: Sapa Sisters is advertised as a Hmong women-owned company who pays their guides well. On top of all that, we even ended up with the same guide they did, eight years ago.

We set off, down into the valley of endless rice terraces.

Soon after, we happened upon two other Hmong women making the trek down from Sapa to their own village. They had been in Sapa selling their handicraft, they said, and they were heading home. It seemed a bit early—we were leaving at 9am, and it was quite a walk down—but I didn’t think more of it.

It was great walking with them. We asked about each other’s families, heard stories of their lives. They helped us over rough terrain, and even made us little animals with leaves from reeds growing alongside the trail. The younger woman gave me one that looked like a llama. A simple gesture, but it touched me. I proudly displayed it in my shirt pocket.

I was surprised to learn that our guide didn’t speak Vietnamese! She spoke her native Hmong language, of course, and then picked up English from travelers. She also couldn’t read or write—never got to go to school.

We walked and walked and walked. Along rice paddy banks, on dusty trails, by sparse government-built infrastructure, and sometimes uncomfortably close to water buffalo.

Everything changed once we stopped for lunch.

Just Another OMTA

It’s my fault. I really should have seen it coming.

We had discussed beforehand what itinerary we ought to do, and had agreed to cook lunch at our guide’s house. But when we arrived at the lunch stop, it didn’t quite look like a house.

Instead, it was a huge room, full of dozens of other tourists. Everyone from all kinds of different trekking companies was being funneled to this spot, where an entrepreneuring family had set up a tourist-friendly dinging room and menu above their living quarters, where they pumped out big volumes of two dishes.

After we sat down, we were descended upon by a hoard of Hmong women who wanted to sell us their handicraft. At the front of the pack: the two women who had walked down with us from Sapa. Their expressions, which had seemed so genuine before, were stone cold.

As this was my first real OMTA in Vietnam, I hadn’t yet learned that you should first read reviews of an activity to learn about the scams. Here’s Sapa’s main one: people identify you as targets in Sapa city, attach to your group, befriend you, and then guilt you into buying trinkets from them at the lunch stop. It’s a long con.

And it totally worked. My simple naïve brain couldn’t handle this emotional transformation. I’m going to out myself for the completely sheltered world existence I have led to this point: despite being over thirty years old, I have never once seen anyone do the emotional 180 that our two Hmong friends did.

It’s not that I blame them. Would I do the same thing in their position? Almost certainly. But what I’m trying to impress upon you is that this moment broke some kind of fundamental, childish belief in emotional authenticity that I still carried. When I’d been scammed before, it was always obvious that the scam was happening. And in every bad situation, people at least seemed to be emotionally consistent: this bus driver doesn’t like me, so he’s mean; this executive is dodging questions because it’s in his interest to; this vendor knows they can make a quick buck if they inflate the price, so they do so with a deadpan.

Not so with this situation. It was like being confronted by completely different people.

As I looked around afterwards, I noticed several people displaying the same leaf-constructed llama that I still had in my pocket. I felt like such a fool. Hitting the trail after lunch, I left it by the side of the road, and with it a little bit of my own stupid naïveté. I wasn’t bitter about the money—it wasn’t much—but that what seemed like friendship was so convincingly faked and then pulled away. I never saw them again after the sale.

Afterwards, I asked our guide if she knew them. Somehow, given our group’s camaraderie, and how small the villages were, I assumed she had. She said she’d never seen them before in her life.04

Homestay

The rest of the trip unfolded similarly. Our homestay was with someone who—imagine the coincidence—just happened to be a relative of our guide. Rather than hanging out with the family, we were never invited inside their home. We stayed with other tourists in separate shacks, under the advertised mosquito nets, paying for beers out of a fridge with a price listing on top. We ate outside.

Was it still cool? Yes. We saw loom weaving, chickens, family dogs who they told us didn’t have names, and an apparatus that makes alcohol which—despite my strong preference to avoid going blind—I drank. The hosts couldn’t speak a word of English, but were still clearly doing their best to be accommodating.

But Something Felt Off

The numbers didn’t add up. Where is the money going?

Our guide had been working with Sapa Sisters for over ten years, and guiding treks for over fifteen. She told us she treks most days of the week. For two days, with a reasonable tip, we paid over $200 US. Some of this, of course, goes to the company, to the lunch provider, and to the homestay family. But given her descriptions of the kind of conditions that they lived in, and seeing what the local prices for goods and services were, it just didn’t make sense that she could be working for those rates for that long and not see more money coming her way. From what we saw in the area, the if we had paid around 1/10 of that, the numbers would have made more sense.

She had told us about a previous trekking company she worked for that paid terribly, and tried to scam her out of her last wages. It was difficult for her to do anything about it, with not being able to read or write. Eventually a friend went with her to Hanoi—one of the few times she’s ever been— to demand her final pay at their office. I can’t remember what those numbers were, but they were so incredibly low that it made the amount we were paying seem ludicrous. Ludicrous that it didn’t seem to be helping people here more.

I couldn’t stop thinking this throughout the trek. Where is the money going? It just felt wrong in my gut. I wanted to believe we were helping empower indigenous women. All the website branding says so. And women have it real bad. Little or no education; stories of abusive husbands—both physically and verbally—and several women had bruised faces; if divorce happens, they lose the kids, and if the ex husband doesn’t like them (the kids), they’ll grow up without clothes or schooling; and husbands cheat, but because the results of divorce are so heartbreaking for the kids, separating is rare.05

This money should be life-changing. But it doesn’t seem to be. Where is it going?

Trekking Back

The rest of the trek sort of sputtered out. Our guide had two kids, including a baby, and she seemed really worn out. Halfway through the second day, she had us trudge up to the nearest road, get in a van, and we rode back to Sapa and said goodbye.

But to be honest, we were OK with it. By the second day, it felt like we’d talked about everything we could talk about.06 And the scenery is pretty, but after many hours of walking, mostly unchanging.

Back in town, we found a delightful café at which to kill time. In a similar turn of events, Julie thought she made a friend who actually just wanted something from her.

We finished with a truly weird visit to Lao Cai—can’t explain, just go there sometime and try to find a place for dinner07—and an equally sleepless train ride back. That’s Sapa.

Brief Reflection on Sapa: The Tiny Agony of Inauthentic Experiences

I remember once finding a great definition of what hipster means, exactly: fetishization of the authentic.

Seeking authenticity feels inevitable in travel. And it’s why I struggled so much to appreciate OMTAs in Vietnam, Sapa included: they felt decidedly inauthentic. You expect to see culture happening in situ. Instead, you find an experience that has been manufactured for you and the dozens of tourists shepherded into the same room.

It’s tricky to write about this08 without sounding completely ungrateful. So what if it wasn’t authentic? You went, you saw, you ate, you talked, you photo’d. Isn’t that enough? The wild, wild luxury that is extended travel shouldn’t be forgotten for a minute. Plus, there’s an amount to which a traveler needs infrastructure to get them through places where they don’t speak the language and don’t know the customs. This guidance will always shape the experience.

But I think if you’re honest about it, you have to draw the line somewhere. Why are you traveling? What do you want that you can’t get from watching the Discovery channel? If you want photographs or a vacation, that’s fine. But we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking we’re experiencing something we’re not.09

Some folks we met in Hanoi were headed way northwest, out past Sapa, to do the current fringe of authenticity seeking tourism: riding mopeds to villages that didn’t have well-oiled trekking programs. As established as Sapa was, it was still hard enough for me to figure out logistically that I thought, no way, can’t do that, not this trip. But I know why they did it.

Here’s a formula: go the first time and do the OMTAs. Visit the sights, get shepherded into big buffet rooms with other chumps, photograph the things. Go off the beaten path when you can. But also: talk to locals and young travelers. Learn where they’re going. Find out what is interesting but hasn’t yet made it on all the travel bloggers’ top ten lists. And maybe, if you come back for a second visit soon enough, you’ll find something true.10

Footnotes

It will take you a while to figure this out, but it seems the way trains work in Vietnam is that different companies own and operate different cars on a single train. So while there may be, say, only one nightly train from Hanoi to Lao Cai, many different companies will sell tickets aboard their own cabins on their own cars on that train. Not knowing this makes the process extremely confusing. Knowing it, it’s still confusing. ↩︎

I sound like a prude. I have perfectly adequate memories of sharing sleeper train cabins with strangers on several longhauls through Germany in '12. Some differences I’m weighing this time: (a) I’m less functional without sleep than I was ten years ago, (b) I’m more worried about theft in Vietnam than Germany, (c) we were transporting more valuables, like laptops and a nintendo switch, (d) the train cabins were small enough that with our suitcases and backpacks, it was tricky to fit two of us; four + luggage would have required human Tetris. This was one of the few instances on our trip so far where (backpacking) backpacks are truly better than a suitcase + backpack. ↩︎

I knew Julie and Carlos back in '11/'12 when we were all studying in Zurich together. I haven’t kept up with them, but their travel blog has been an inspiration. If you’re reading: hi guys! ↩︎

It turns out that you can tell your guides in advance that you don’t want to be followed by people trying to make a sale, and they’ll tell candidates not to. ↩︎

Plus, you have the everyday struggles: even minimal government fees for paperwork are hard to afford; we were also told the Sapa hospital was full, so our guide had nowhere to take her baby that was currently sick. ↩︎

Our guide told us a lot more about her life than I’m writing here. It was genuinely interesting, and cool of her to share that much with us. (Out of respect for her privacy, I won’t repeat it on the internet.) But we pretty quickly came across the limits of how much we could communicate; which questions we could ask and would be understood. And we shared so little life experiences in common that it was hard to find a lot to discuss once we reached those linguistic barriers. ↩︎

I’m really not going to explain it, but I will describe one funny thing that maybe kind of sums up the experience. We took a shuttle down from Sapa down to Lao Cai (no van vomiting this time; I guess people find downhill easier). We were last picked up so only two seats were open, one next to the driver, which I took. The driver got chatty but didn’t speak any English, so he started using Google Translate on his phone to talk to me. Seemed like a good guy, offered me toffee at some point. Then at some point he got a call which made him visibly agitated. Needing someone to rant to, he started furiously Google Translating to me: “They say we left someone. It is not my fault. There was no one else on the list. It is not my fault,” showing me his list of papers and pressing buttons on his phone while we’re blasting past semis around cliff-side turns in the pitch black. My life quite literally in his hands, I agreed with him as emphatically possible. “It’s not your fault. I’m sorry. Yes you did the right thing. Wow it sure is a dark road, huh?” Somewhere above us, a huge bridge across the valley loomed, half built. ↩︎

Cue tiny violin for me ↩︎

This is why I often get the most jazzed when we wander into a random, weird part of town. Finally, something real! I’ve had good luck with places that start with “New:” New Belgrade, New Taipei. ↩︎

Or, shortcut this by being a backpacker and staying at hostels. Then you can keep your itinerary open enough that you just figure this out right when you get there. ↩︎