Building an ECS in TypeScript

Why build an ECS? Why TypeScript?

There are several questions we should ask ourselves upfront:

- Why build an ECS?

- Why build a game engine at all?

- Why use TypeScript?

Why Build an ECS?

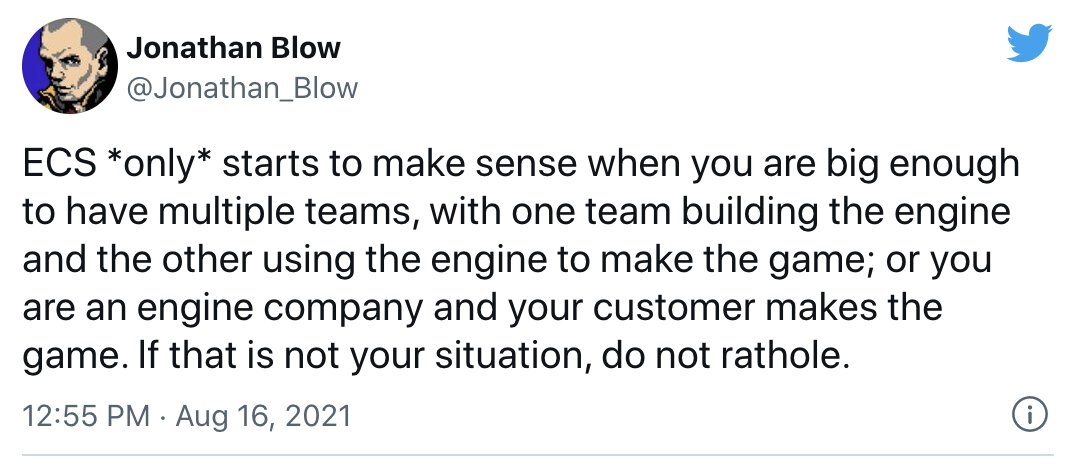

Game engine architectures seem to be a mini religious war in programming, much like Emacs vs Vim, or tabs vs spaces. You can find critiques by prominent game industry figures:

Here’s an example of one such big company (Blizzard) using ECS to build a prominent game (Overwatch):

No need to watch this now, just squirrel it away if you’re interested.

So, is it true that ECS is only good for big teams?

To be honest, I don’t know. I don’t work in the games industry, and I don’t have that much experience. So all I can draw on is my own experience.

My experience is that ECS is a simple design that scales beautifully with the project. I wrote a simple ECS when I first started programming Fallgate (I’ll show you what I wrote in the next post), and it was fun and easy to work with for two years of programming. If you’ve worked on a programming project before, you might realize that this is, in fact, an absolutely wild accomplishment for a design pattern. Usually, I run into serious design flaws with my code after about a week. In the course of the two years, I never had to replace the ECS, and it felt natural to keep building on top of it.

Aside: ECS vs Data Locality

When I see discussions of ECS, I commonly see people conflating two ideas:

- ECS as a design pattern for structuring code

- Placing data contiguously in memory for good cache performance

If you’d like to read more about each of these, Bob Nystrom has great writeups on what he calls the component and data locality patterns. His treatment of these gets at their fundamental differences, but be aware neither is quite what we’re doing here with an ECS (which he mentions).

Now, #2 (data locality) can be important for performance.01 And both can go hand-in-hand. However, my focus here is purely #1: using ECS to structure the design of your codebase.

Building small (2D) games as an independent or hobbyist developer, I think it’s worth exploring design patterns that help you think and structure your code, without worrying about performance. In my experience, ECS is a straightforward, natural way of thinking about how to compose entities in a game world. Once you do want to worry about performance, you can measure your code and see where the bottlenecks are.

Aside: ECS Strengths and Weaknesses

Is the ECS a perfect architecture?

As usual, I think the answer is: it has pros and cons depending on what you’d like to achieve. As a beginner, I found it a great architecture to get started with.

I found ECS worked very well for:

- adding common state to many objects (e.g., health, damaging, moving)

- giving common logic to many objects (e.g., attacking, moving, dying)

- generating a game world from data files (e.g., a tile map and .json files)

I found ECS didn’t naturally help with:

- managing animations (trees and state machines)

- events

- scripting (e.g., cutscenes)

- GUI management

- particles

- Systems communicating with each other

- chunks of code that need to update every frame, talk to each other, and access other global objects, but don’t interact with components

In my mind, the areas where ECS didn’t help were an opportunity for defining other parts of the game engine, and building nice ways for them to interact with the ECS. Because my design was ECS-centric, those other aspects of Fallgate—like events, scripts, and animations—varied in how well I built them, and how well they worked with the ECS. Some, like particles, worked out great, and played nicely with the ECS. Others, like events and animations, ended up more like warts. If I was to work on a second engine, those would be the design areas I would focus on improving the most.

But okay, we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Why Build a Game Engine at All?

In general, I think that if your goal is just to make games, you shouldn’t write game engines.

But people write their own boutique engines all the time. Why? Are they fools?

I can think of three main reasons people do it.

1. Skip Setup Hell

This sounds like a complete paradox. You think you’re going to lower the setup cost of making a game by building an engine first?

But let me tell you, if you’ve ever tried to use a game engine like Unity, there’s a horrible, multi-day or multi-week slog of trying to figure out the damn software. I’ve bounced off seriously trying at least four times over the years—and I mean serious, like multi-day efforts.

You’re reading potentially mediocre documentation, learning a specialized languages or APIs, struggling through bloated tutorials, and trying to figure out how the game engine designer decided you should think about things.02

None of this is fun! It’s the worst part of a project (in my opinion).03 It can be so bad that you can give up altogether. I know I have.

For a precious little idea, giving up is death. It’s the end.

So what if, instead, you pick the lowest barrier to entry you can find? Something with a tiny API that you can get programming with immediately? (In other words, the angle here is for someone who knows how to program, but isn’t making games yet.)

I found this with pixi.js. It’s a Javascript library that, at its essence, lets you say, “draw this .png at location (x, y) on the screen.” And you know what, that’s really all you need to get started. Throw in a loop that updates 60x a second, start moving the image around, get keyboard input, and you’re off to the races.

So, it’s safe to say that this is the bucket that I fall into (though I’m guilty to some degree of all three). I built something myself because I just wanted to get started, and I didn’t want to risk yet another project dying as I spent another four days going through tutorials for deprecated versions of bloated engines.

But the only reason this would be remotely possible is reason #2 people build their own engines: it’s actually not that bad.

2. What Is a Game Engine Anyway?

“Game engine” is one of those words, like “framework,” that’s so vague as to be nearly meaningless.

For people building 3D games, the engine has to be comparatively massive. The process of rendering realtime 3D worlds, and managing a whole pipeline of 3D assets (models, skeletons, textures, shaders, scenes), is one or two orders of magnitude more complex than a 2D pipeline, where you basically have textures and 2D maps. Add on top of this the fact that 3D games tend to correlate with bigger games in general, which means more complex simulation systems, game logic, content authoring tools—the list goes on. And look, I’m not even qualified to write these lists. I’ve never worked on a 3D game. This is an outsider’s perspective.

But for a 2D game, the process is much more constrained. And I think that a lot of what you build in a 2D game is stuff the engine isn’t going to provide you in the first place. All the logic of “how the game works” and “what the game is” are things you’d have to design and build anyway, even if you used an existing engine. The only exceptions are cookie-cutter game making tools (like building an RPG in an RPG making tool). So using a game engine might help—especially if you’re inexperienced (I’d still count myself in that bucket)—but maybe not by that much.

This idea is something that I only really realized listening to Maddy Thorson and Noel Berry talk about making Celeste. I can’t remember the exact source—I think it was in a Twitch livestream—but they were asked whether they used a game engine. And they kind of laughed and said something like, “no, it wouldn’t have helped.”04

So anyway, to bring this back around, the idea isn’t that there’s a fixed target called a “game engine” that you go out and build, and then you build the game on top of it. For my case at least, the engine is the broader codebase that evolves around the game as you build it.

3. It’s Fun

“What I cannot create, I do not understand.”

– Richard Feynman, just before wasting his next 15 years building a game engine.

While I primarily came from reason #1 (getting started), and I think the Celeste developers came from reason #2 (it’s not that bad), I think someone like Jonathan Blow—who has worked on not only a new 3D engine, but a new game programming language—ultimately falls into this third category.

People like building shit. It’s fun. It’s really fun.

This is the answer nobody will give you. It’s the same reason your one friend who is obsessed with Linux bothers to recompile the drivers for their bizarre distribution you’ve never heard of, uses some text-only free software music player, and types with Colemak key bindings. They’ll tell you it’s because of privacy or freedom or something, and while that’s not untrue, they’re not being honest with why they’re really doing it in the first place. They’re doing it because they love it.

For a AAA studio, there’s probably a real need to invent new technology. Breath of the Wild probably required some wild magic to run a world of that size that well on the Switch. The Elder Scrolls games famously have intricate quest and content building software that ships with the game itself. And any kind of real-time multiplayer needs a serious physics × networking backend, even if it’s built on a mainstream engine.

But small indie shops making their own engine, I submit, do it because they want to. Above smaller reasons like getting away from object-oriented programming, there’s a deep drive to understand how things work, and to build things yourself.05

Summary

Just to be clear, I’m proposing mostly that we build a tiny ECS engine for 2D games because it’ll be easy to get started (#1), and we’re not missing a ton like we would in 3D games (#2). But secretly, let’s admit it will be fun (#3).

Why use TypeScript?

This one’s easy:

- If you want to easily share your game with others, it’s hard to beat sending them a web page

- JavaScript it still the de-facto language of the web

- TypeScript is a huge upgrade to JavaScript

Publishing mobile apps requires laborious app approval processes, and $100 (at least for iPhones). Game consoles are even harder—you can basically forget about it. Rather than trying to get people to download and run software, you can just send them a URL.

If this doesn’t convince you, no problem, I get it—I’d also love to build games for consoles someday. So here’s one more pitch: think of it as prototyping. A fun TypeScript thought experiment. You can take all this and move it to C# or C++ or whatever you want afterwards.

All right, we’ve got all that covered. Let’s get to making an ECS!

Footnotes

Bob Nystrom writes that he gets a 50x speedup (!) when implementing data locality for a simple update loop. So yeah, memory access—and profiling—really matter. ↩︎

The other struggle I have is that it isn’t easy to peek under the covers for other engines. I want to know a bit more about what’s going on, but learning how to peek into the internals of an engine is yet another thing to learn and understand. ↩︎

I just went through this setting up a multi-target project with three.js, webpack, and TypeScript, so the pain of setup hell is freshly in my mind. These are all mainstream technologies, but I think the more things you intersect, the worse of a time you’re going to have. Just going through this for days almost made me give up entirely—it’s really a small miracle I made it through. ↩︎

To tell you the truth, I’ve wondered a lot about that after I heard it. Could this be a case of underestimating how much they were reinventing when making their own engine? Was it that they had so much experience making other games, it really wouldn’t have saved them time? Or was it that they actually loved making the engine themselves? The answer is probably a mix of the above, but I do still wonder about the distribution. ↩︎

Just be wary of building an engine without a game! Engines have many shapes, and games are vast software. ↩︎