A Modest Proposal: Let’s Stop Lying To Each Other in Our Research Papers

How we can fight spin

I was reviewing for ACL01 last week, and it was a particularly depressing time. It was depressing because it made me remember how much we lie to each other in our research papers.

It goes like this.

The Model

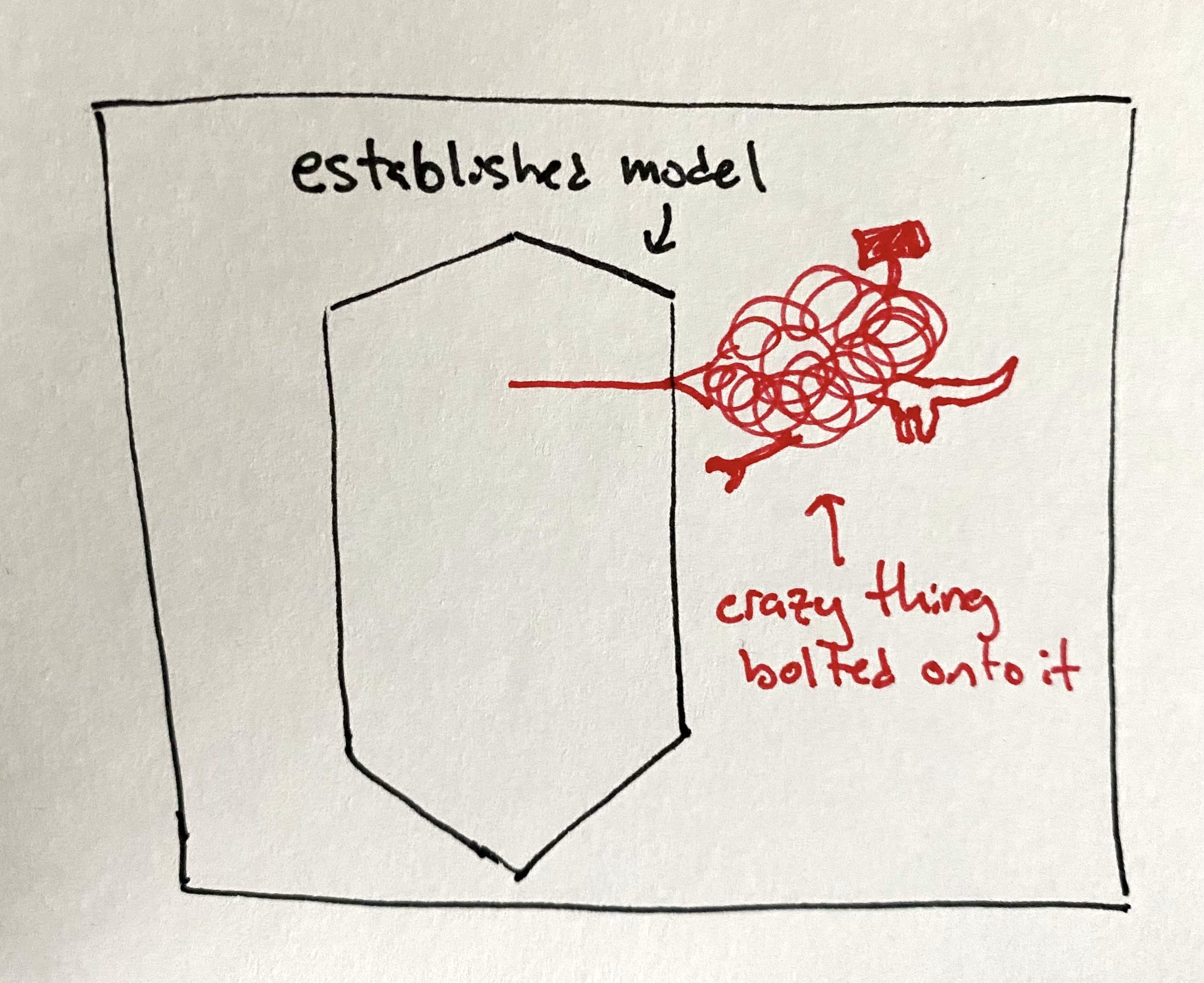

Say you you’re reading a paper that presents a new NLP02 model. The model takes some ubiquitous neural network architecture—technical: like the LSTM or the Transformer—and bolts something onto it.

Components: wrench, hammer, half of dog.

Let’s pause briefly to imagine you’re considering working on the same task presented in the paper—for example, sentiment classification, or image captioning. Which will you pick: the established model, or this new idea which is “established model + crazy thing bolted onto it?”

Already, the established model has a bunch of major advantages:03

- it probably has fewer bugs

- it’s much more likely you can actually just run the code

- it’s been battle-tested in other domains

- there’s a variety of community wisdom, GitHub issues, StackOverflow posts, etc., around running it

- it doesn’t require any special auxillary data, training regime, or boutique preprocessing, which the new thing probably does

- the new thing is probably slower

Add to this meta-analyses that show bolted-on tweaks aren’t actually doing anything (e.g.: this one for LSTMs, this one for Transformers), and you have a pretty compelling case to stick with the base thing.04

But wait, there is one factor that remains king in how we judge which research papers get published. It starts with “S” and rhymes with “OTA.” That’s right, it’s “state of the art performance.”

The Bait

This new paper offers you better performance. For example, it detects sentiment more accurately, or writes better captions for images. By how much? Well… let me take an example from a paper I was reviewing. I’ll tweak the values and obscure the metrics, but keep the intervals the same:05

| model | score 1 | score 2 | score 3 | score 4 | score 5 | score 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Even Older Prev. Work | 39.2 | 46.3 | 50.3 | 62.9 | - | 140.1 |

| Previous Work | 39.1 | 46.5 | 50.4 | 62.7 | 85.9 | 140.8 |

| Our New Model | 39.2 | 46.5 | 49.8 | 62.5 | 86.1 | 140.9 |

The highest numbers are bolded. (This is standard practice.)

Now, already we’re trusting researchers to run fairly on the test set, and report the right numbers. I’m fine with this—though one paper I reviewed actually reported that they did hyperparameter tuning and model ablations on the test set 🤦♂️. But let’s assume these numbers are honestly gotten and honestly transcribed.

The Lie

Here is what the paper says about these numbers:

“Our method outperforms all existing methods in terms of scores 1, 2, 5, and 6, while having comparable performance in terms of scores 3 and 4.”

Seems harmless, right?

Well, until you actually read the numbers. Let’s look at the metrics they said they won:

- score 1: tied, didn’t outperform all existing methods

- score 2: tied, didn’t outperform

- score 5: higher by 0.2

- score 6: higher by 0.1

OK, so this changes the story a little bit… it looks like two ties, and two numbers that eked out slightly ahead. Well, what about the others with “comparable performance?”

- score 3: lower by 0.6

- score 4: lower by 0.4

Oops, writing and reality have diverged. The writing says, “usually better, otherwise the same.” But just a few pesky inches away, the numbers say, “usually the same, otherwise worse.”

Call it by whatever name you want, this is lying to the reader.

The problem is not that this one paper that did this. The problem is that this is so normal we don’t even usually blink when we read it. In fact, I felt guilty even brining this up in my review.

Interlude to Remind Us We’re Doing “Science”

I just want to pause here and reflect that we are supposedly doing science right now. These are scientific papers. At least in the U.S., we’re funded by scientific grants, which come from the government, which come from people paying taxes. (If you reject that computer science is “science,” and think that it’s actually “engineering,” fine—I think the point stands even more.)

It just makes me think about what if someone was, oh, I don’t know, working on a vaccine, or cancer research, or some kind of hard science with stakes that matter, and tried to pull this kind of baloney. This might be overly optimistic because I don’t know how other fields work, and because of the whole p-value crisis, but I still have to imagine other fields have established a numerical culture where this kind of color commentary simply would not fly.

OK, back in.

We Were Saying How This Is Maybe Worse

So, to recap, vs previous work:

- two scores: exactly the same

- two scores: higher by 0.1, 0.2

- two scores: lower by 0.4, 0.6

Current standing by extremely naïve looking at numbers: pretty much the same, but slightly worse.

The first thing you might ask is, “OK, there are six scores here. Which one is most important?”

I think that is a great question. After all, these are different metrics for attempting to measure how good the model is. Could it be that some metrics are better than others at doing that? (Hint: yes, and the best is not one they do better on.)

People spend lots of time coming up with new metrics to address known deficiencies in previous metrics. They agonize over them, do all kinds of correlations with human judgments, and publish the new metric.

Then what happens? Well, it just becomes yet another column for the results table. There’s no mention of the scads of previous research about which metrics we should care more about. It’s just ✨numbers✨. Oooh, look, some of them are higher!

Current standing by incorporating metric importance: slightly worse.

But, you might ask another question.

Can We Even Say It’s Actually Worse?

How do we know this isn’t just statistical noise? Could the results be basically the same as the last paper? Maybe even the last few papers?

My answer is: ya, it’s probably just statistical noise. Thanks for playing. 🤷♂️

Current standing by remembering statistics exists: probably the same.

But wait, we must have… statistical tests we can run, right? Surely it’s standard practice to—

Nope.

Maybe, just maybe, if you’ve got some eagle-eyed reviewers and diligent researchers, you’ll get statistical significance tests on stuff like human evaluations.06

But on the good old results table, people just look for the highest number according to (waves hands) decimal places, bold it, and move on.07

Are Things Really This Bad?

Yes and no.

There’s a ton of great research—even some Real Science—going on out there, and lots of people that agonize over this and get it right.

But so many papers just blow past this. The field’s obsession with higher numbers, coupled with a few dominant models that make it hard to truly get higher numbers, leads to this bizarro world where a research paper:

- gets basically the same numbers

- can’t lie about the actual numbers, fearing they’ll get found out

- instead writes colorful language about how the numbers mean they’re better

Then,

- everyone who is in on the game ignores it entirely

- everyone who is not in on the game—funding agencies, disinterested hiring and promotion committees, the general public—just sees ✨research✨ happening

- the paper mill continues

This has led to an unbelievable amount of noise in published research.08 And as a researcher, you have to develop this skill of actively mistrusting basically everything you read.

My Call to Action

There are several things we need to do. I will outline just the simplest piece here, which is to get our $%*! together on the numbers front.

As a field, we need to standardize:

-

Metric importance. Which metrics we care about more. If a model wins on X but not Y, is it better? We know this already,09 we just aren’t taking it seriously. Right now, papers get to call their own shots, which roughly amounts to completely ignoring this.

-

Uncertainty statistics. For each metric, what is some statistic we can measure to basically get “error bars?” There’s no established measure we run on each metric. People don’t even agree that there should be one, because they believe these metrics measure something like a child’s score on a test. We can collectively think about this for five minutes and realize, oh yeah, any test set is sampling from a distribution, and so when you average 100 or 1,000 or 10,000 numbers and come up with some value, we can take that process into account and include a measure of uncertainty.10

- Thresholds for “better.” For each metric, given the corresponding uncertainty statistic, for what difference are we allowed to say X > Y? We intuitively understand that 62.000000001 isn’t that different from 62.000000002,11 but for some reason, we’re still allowed to write that 62.1 is significantly worse than 62.2. This means picking a cutoff for the metrics.

If we can do this, it removes the fudgework from deciding whether model X > model Y given the availability of metrics A, B, and C. And if we make it dead-simple to do, like running automatically in standard evaluation scripts, people will actually report it.

Important: I’m not saying we need to use these metrics as a way to gatekeep what gets to be published. I will be the first person to tell you that my own research is not built off getting the highest number on leaderboards. We need a variety of research styles, including new angles, new tasks, model dissection, and thorough analysis.12

All I’m saying is, I think it’d be a bit less embarrassing for everyone if, when someone new to the field—like an undergrad who just joined the lab—holds up a paper and says, “we should start here, because they got the highest number," we didn’t have to take them aside and sadly say, “Oh kid, I’m sorry, nobody told you yet… We’re all just a bunch of lying baboons.”

Epilogue: What’s the Bigger Picture

The researchers who wrote this paper aren’t at fault, really. They’re just playing the game. But the game is made collectively, and we can change it. In academia, this happens somewhat slowly, but it does happen.13

Stay tuned for more on this.14

Footnotes

ACL is one of the three top-tier (most prestigious) conferences in our field. If you’re not familiar with academic computer science, we publish our research in “conferences,” not “journals,” mostly because the turnaround time is faster, I think. ↩︎

NLP is “Natural Language Processing,” a field in machine learning (or now, “AI”) that studies using computers to do stuff with human languages (mostly English). ↩︎

Established models being so good is actually a pretty recent phenomenon, largely due to big consolidated efforts. ↩︎

When I started my PhD, posting your research code on GitHub at all was novel and exciting. For years profs. would infamously say something like, “well, the code’s online right? Just run it.” Which, to be fair, having code available is usually probably slightly easier than reimplementing it. But then, dozens of hours later spent slogging through undocumented research code with hardcoded paths and missing files… fortunately, I think profs have weathered enough complaining at this point they know “code online != can run it.” But this just reinforces the gap between major popular repositories and one-off blobs of deep learning gunk published by schmucks like me. ↩︎

If you’re paying close attention, “tweaking the values but keeping the intervals the same” should make you a little suspicious. After all, 0.1 vs 0.2 is pretty different than 100,000.1 vs 100,000.2. Suffice to say, I kept them close enough for jazz (= statistics by a computer science person). ↩︎

Human evaluations are where you ask humans to judge whether system A or system B is better. This has a whole suite of problems on its own, which I will save for another rant. ↩︎

Tomfoolery around bolding numbers abounds. You will see hilarious tactics like migrating better numbers to other sections of the table so as to avoid bolding them, or just flat out not bolding metrics the proposed work didn’t win on. ↩︎

Check out Troubling Trends in Machine Learning Scholarship (Lipton and Steinhardt, 2018) by some folks who cared enough about these problems to actually write a paper about it and get (other) famous people to review it. I really applaud this, though I also roast them a bit elsewhere. ↩︎

Great analyses of metrics and human judgment abound. Here’s a recent nice one: Tangled up in BLEU (Mathur et al., 2020). ↩︎

Coming up with statistics for all of our metrics is above my pay grade and, more importantly, beyond my abilities to do stats on a whim. But for inspiration, check out bootstrap sampling, or common statistical tests like students t-tests. ↩︎

Physicists, you stay out of this. ↩︎

As someone interested both in human evaluation as well as using ML models to score other ML models, I also don’t mean that we should be restricting evaluation just to the currently established metrics. I think continuously questioning how we assess models is a great line of inquiry, and it should keep happening. What I’m talking about is standards for the flip side of the coin: papers that propose new models and just “run the gauntlet of standard metrics” on them. ↩︎

NLP seems to be a bit on the slow side in terms of machine learning disciplines—for example, we still haven’t figured out that the arXiv blackout window seemed like a good idea but sucks in practice—but even we are making some strides: e.g., switching to a rolling review cycle. Maybe some day we’ll even let our reviews be readable (gasp) on the Internet. ↩︎

As in: I wrote more but it made this post too long. ↩︎