Bosnia and Herzegovina

I’ve been anticipating writing this post with the specific mixture of eagerness and dread that comes whenever I take on something that feels important. I learned more about Bosnia than anywhere else I visited, and I’ve felt compelled to share more about it.

If you’d like, you can skip my intro to Bosnia and head right to the travel writing.

Five Bits About Bosnia

I knew almost nothing about Bosnia before visiting. The whole time we were there, I spent almost every spare minute pouring over Wikipedia. The place is so steeped in complex and immediate history that I needed some serious catching up just to make sense of my surroundings.

I’m going to give you the briefest of summaries here. What I’m writing is an amalgamation of what I was told by various guides, museums, and my own reading. I barely have a passing knowledge of any of this, so please take what I write with a grain of salt. All mistakes are my own.

1. Bosnia’s Balkan Neighborhood

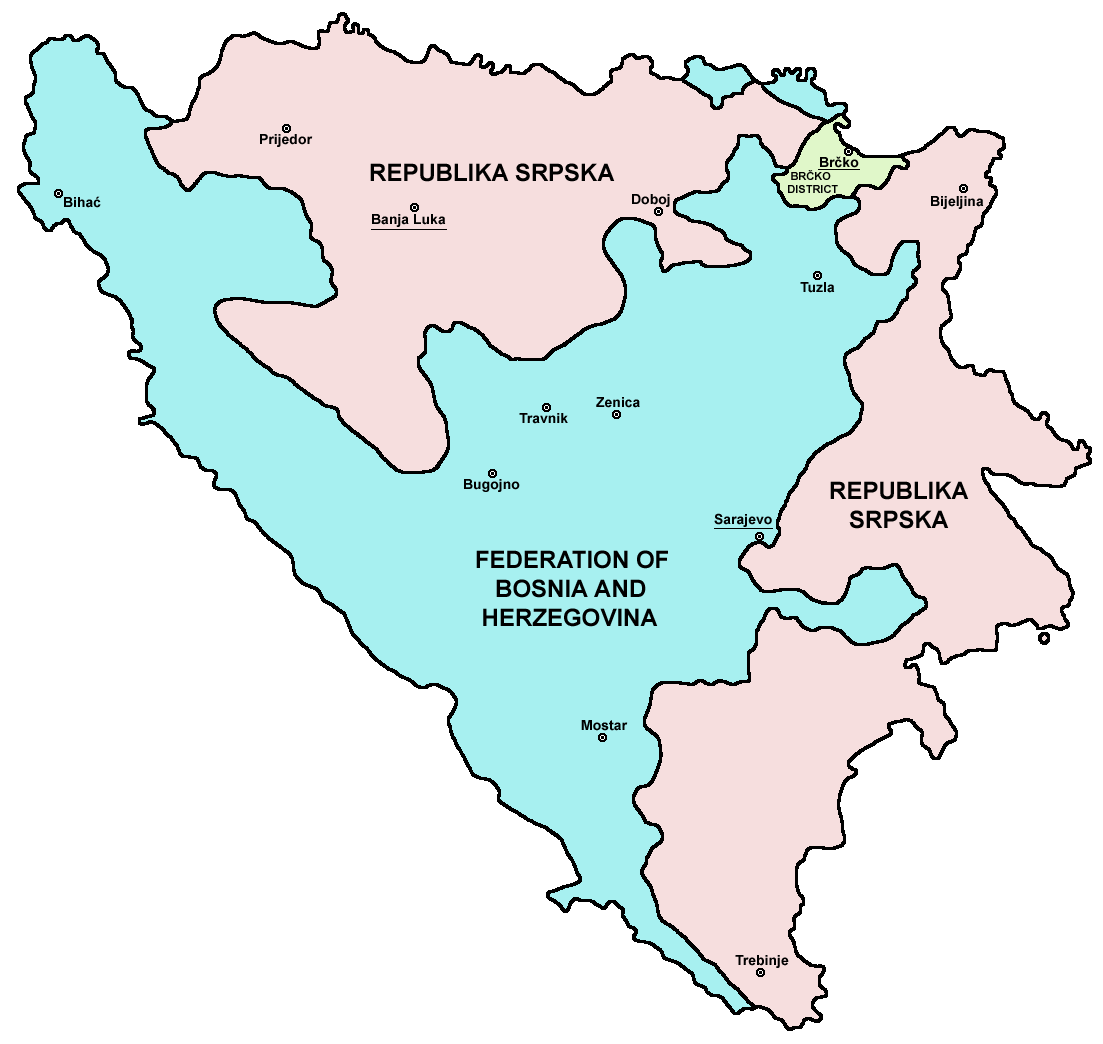

I have Montenegro and Kosovo in a shade of Serbia’s color (red) because, during the formative period of recent history we’re interested in, they were basically controlled by Serbia.

Mainly: Croatia and Serbia.

Amazingly, Bosnia does actually have a wee bit of coastline,01 though it’s so small you can’t even see it here. (You’ll see it on the next map.)

When you ask a local about who lives in Bosnia, they’ll tell you there are three ethnic groups, each paired with its own religion. And they’ll tell you which one they are.

- Bosniaks; Muslim

- Bosnian Croats; Catholic

- Bosnian Serbs; Orthodox

Who Bosnia’s neighbors are will become important for understanding Bosnia itself.

2. Herzegovina Is Not A State

When you see the name Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H), you might initially expect it to be a country comprised of two states, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

This is wrong. Herzegovina is a vague geographical region encompassing the south of the country. It’s never had strict boundaries, and it’s never been an administrative region in B&H.

Dark orange: definitely Herzegovina. Light orange: maybe Herzegovina. Beige: definitely Bosnia. Also, note the little tendril shooting out to touch the Mediterranean. (Image: Wikipedia)

Herzegovina comes from Herzog (German for duke) and -ov + -ina (Slavic02 for land of). So, Herzegovina means “duke’s land,” and the Ottomans called this region it when they took it over from Bosnian medieval dukes in the late 1400s.03

When in the region, I often heard people refer to the country in short as just Bosnia, and I’ll do the same here.

3. The State Boundaries Are Wild

Check this out:

There’s also a shared admin region called Brčko which I will ignore because I don’t know anything about it. I assume the presidents all hang out there. (Image: Wikipedia)

The two states04 are the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Republika Srpska. Still not sure why Srpska is spelled that way, but if you guessed it’s basically the “Serbian Republic,” you were right.

Roughly speaking, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina contains Croats (Croatians) and Bosniaks, and Republika Srpska contains Serbs.

Why on earth is the country broken up this way? I’d like to tell you, but I have one more fact first.

4. There Are Five Presidents

I first thought there were three presidents, which already blew my mind.

The country itself has three presidents. This is, according to the constitution, so that there’s one Bosniak, one Croat, and one Serb. The Federation of B&H, where Bosniaks and Croats live, elect the Bosniak and Croat presidents. The Serbs in Republika Srpska elect the Serb president. Then, the presidents take turns being the super president.05

But it gets wilder. The Federation of B&H and Republica Srpska each have their own president as well. This gives us a grand total of five presidents, and sets the stage for what, to me, seemed like the biggest struggle B&H faces right now: political deadlocks.06

Wild state divisions and five presidents. Why are things this way? The reason is a major conflict—and humanitarian crisis—that happened during my lifetime, but when I was too young to have any awareness of it. The Bosnian War.

5. The Bosnian War

Talking about any of this stuff is like unraveling a fractal. The Bosnian War was a multi-part complicated war, with three main sides, and multiple countries directly supporting the different sides. And the whole war was itself part of the breakup of Yugoslavia, whose armed conflicts are dubbed the Yugoslav Wars.

So, let’s touch on everything super briefly.

Yugoslavia was a mega-country for most of the 1900s. After WWII it ended up as this socialist state awkwardly sandwiched between the West (USA, Western Europe, etc.) and the USSR, but non-aligned with either. It contained Bosnia and all its neighbors that I put in that map above, plus Slovenia (NW corner) and Macedonia07 (SE corner).

Then, Yugoslavia exploded. Into a bunch of different countries. Starting in '91, it fractured—basically by ethnic group—in a process so famous they even coined a term after it: Balkanization. Here’s a graphic of that happening.

B&H is the gray one that ends up the middle. Not pictured: several Yugoslav Wars in this process. (Image: Wikipedia)

Bosnia & Herzegovina was (and still is) a multi-ethnic melting pot. Croatia (to its left) and Serbia08 (its right) allegedly said hey, we’ve got a bunch of Croats and Serbs in this place, wouldn’t it be nice if we split it up and took it for ourselves? We just have to kick the Bosniaks out first.

Enter the Bosnian War ('92–'95), which involved Croats (backed by Croatia) coming up and taking territory from the south west, and Serbs (backed by Serbia) taking territory from, well, basically everywhere else. This left the Bosniaks out there fighting two wars at once. Eventually international forces come along and start bullying Croatia to cut that shit out, so after terrorizing the heck out of Herzegovina (e.g., in Mostar), they join forces with Bosniaks to fight against the Serbs (e.g., in Sarajevo). Tl;dr, a whole bunch of awful things happened, and other countries eventually convinced everyone to stop fighting. This took literally thirty-five ceasefire attempts. Now the country is carved up roughly 50/50 into two states that don’t not look like the military lines from the war. One is that tense Bosniak + Croat alliance, and the other the Serbs that were fighting them.

The state of things is as awkward as you’d expect if you just stopped fighting a war and split up your country with your opponent. These are people who you weren’t just at war with, but who were committing war crimes (incl. genocide via ethnic cleansing) to you. Even in the Federation part, Bosniaks and Croats go to separate schools, attend different universities, use different post offices, even run different power companies.09 It has the mood of a bitter truce, carved up by ethnic lines and regularly reinforced by nationalist10 rhetoric.

Sarajevo

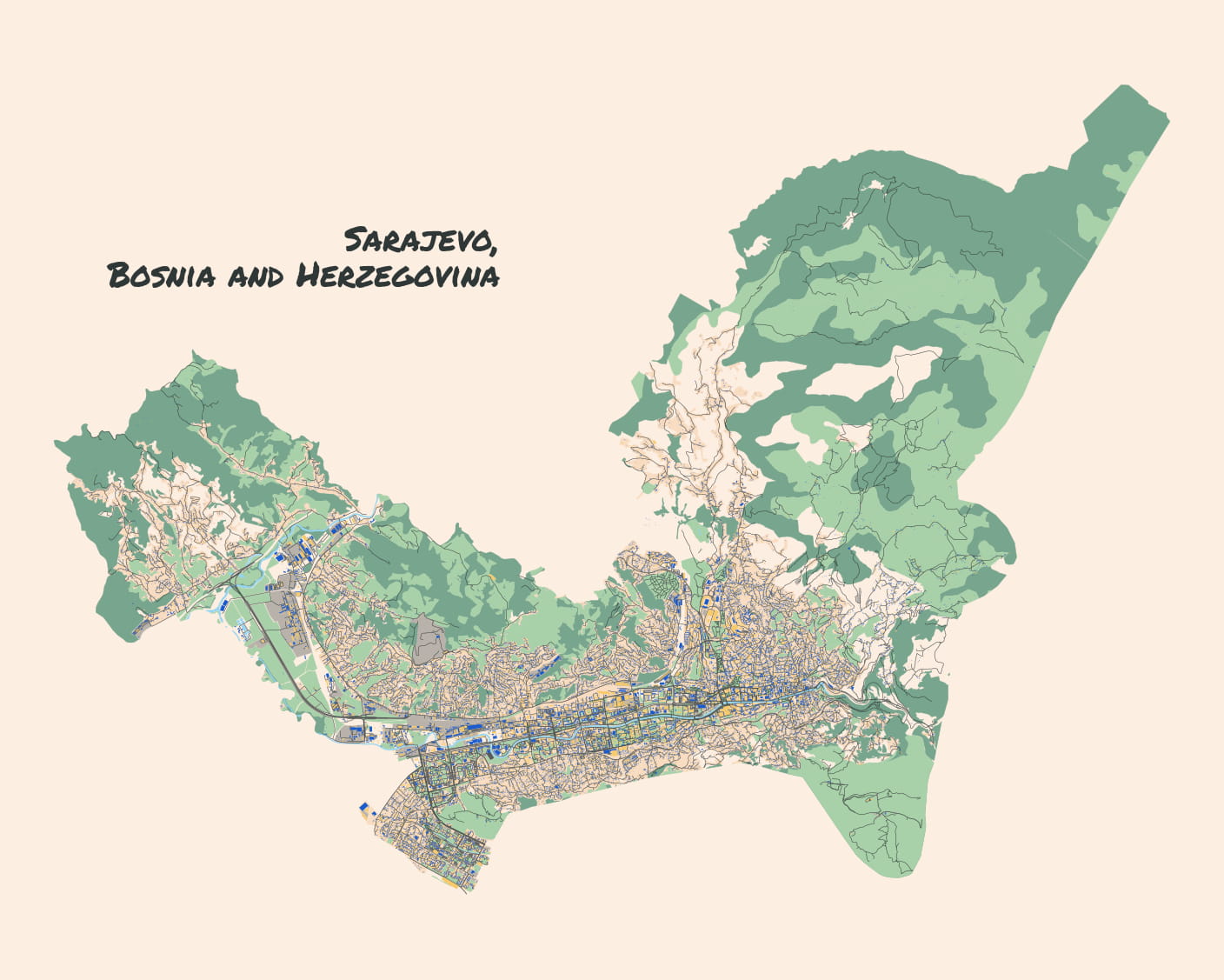

Flying into Bosnia’s capital, I was amazed by how beautiful the northern country is. It seemed like there were endless tree-blanketed hills, rivers, and little patches of towns.

Getting Into Town

The airport experience in B&H was pretty smooth, so I was optimistic we’d have no trouble catching the airport bus into town. Sure, it only came once every hour and a half, but we arrived and found the stop with time to spare. So we set up camp and waited.

And waited. And waited.

Eventually, two Turkish tourists came over to wait with us. After long enough, we all agreed it wasn’t looking so hot that the bus actually existed.

Taxis in Bosnia are, you guessed it, also notorious for scamming you. We weren’t thrilled about the prospect, but it was starting to rain, and we didn’t have any other options.

As luck would have it, a weathered guy walked over to us and encouraged us to get in his car. He’d parked outside the lot so as not to pay the toll, and was offering a fixed price to get into town. He had about seven teeth—and a similar number of English words in his arsenal.

We went from being totally unconvinced it was a good idea, to riding in his car, in the span of about ten minutes.

During the car ride, he started making elaborate hand motions and whistling sounds. I eventually figured out he was warning us not to walk on the streets, lest pickpockets take our wallets. Well, too bad dude—our whole MO was to walk around the city for several days, and we’d be damned if this was going to stop us.

Let’s Talk Sarajevo

You can feel Sarajevo’s history walking around. Some areas will feel like a classic European town, stonework and hills and old homes.

Notice (top photo) something you don’t see much of in Europe, though: a mosque’s minaret. More on this later. Bottom photo: city hall. Though it looks stylistically similar to Moorish architecture you’d see in Spain, it’s actually “pseudo-Moorish,” built by the Austro-Hungarians wiki.

If you get a little elevation, you can spot gorgeous green valleys rolling into the distance, and look back into town to see Muslim cemetaries and orange-shingled residences on serpentine roads.

Passing through the ancient famed bazaar (the phonetically intimidating Baščaršija; no photos, sorry)—mostly hawking for tourists these days—you’ll encounter brutalist infrastructure and rusting administrative buildings, markers of past Yugoslavia.

If you keep going along the river, you’ll reach the heart of foreign money’s spend: glass behemoth buildings filled with malls and offices, and gigantic ads that somehow seemed even more out of place than usual. Oracle, Microsoft, and Bloomberg; KFC, Heineken, and Jack Daniels. I think the surge of post-war international investment has dried up since things haven’t taken off like they’d hoped.

“Jerusalem of Europe”

Sarajevo’s most notable historical quality is probably its religious diversity. Bosniaks are mostly Muslims, but the city has a long history of several religions coexisting. There is technically at least one synagogue still around, but it seemed to me like Islam and Christianity (Catholicism for Croats; Eastern Orthodox for Serbs) were the major players at this point.

War and the Srebrenica Massacre

Just like Jerusalem—and, oddly enough, Jerusalem was our next destination after Bosnia—Sarajevo’s present feels inextricably tied up with the violence of its past. Go into a shop, and you’ll find metalworkers building crafts from ammunition shells from the war.

We took a long city tour, and they pointed out another prominent historical landmark. The place where the shot that kicked off WWII was fired: the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand happened by the unassuming Latin Bridge.

But most of what we learned was about the Bosnian War. Sarajevo was under siege from 1992 to 1996.11

The Siege of Sarajevo] lasted three times longer than the Battle of Stalingrad, more than a year longer than the siege of Leningrad, and was the longest siege of a capital city in the history of modern warfare.

A siege so long, and so recent, you immediately understand why the city is in the state it’s in.

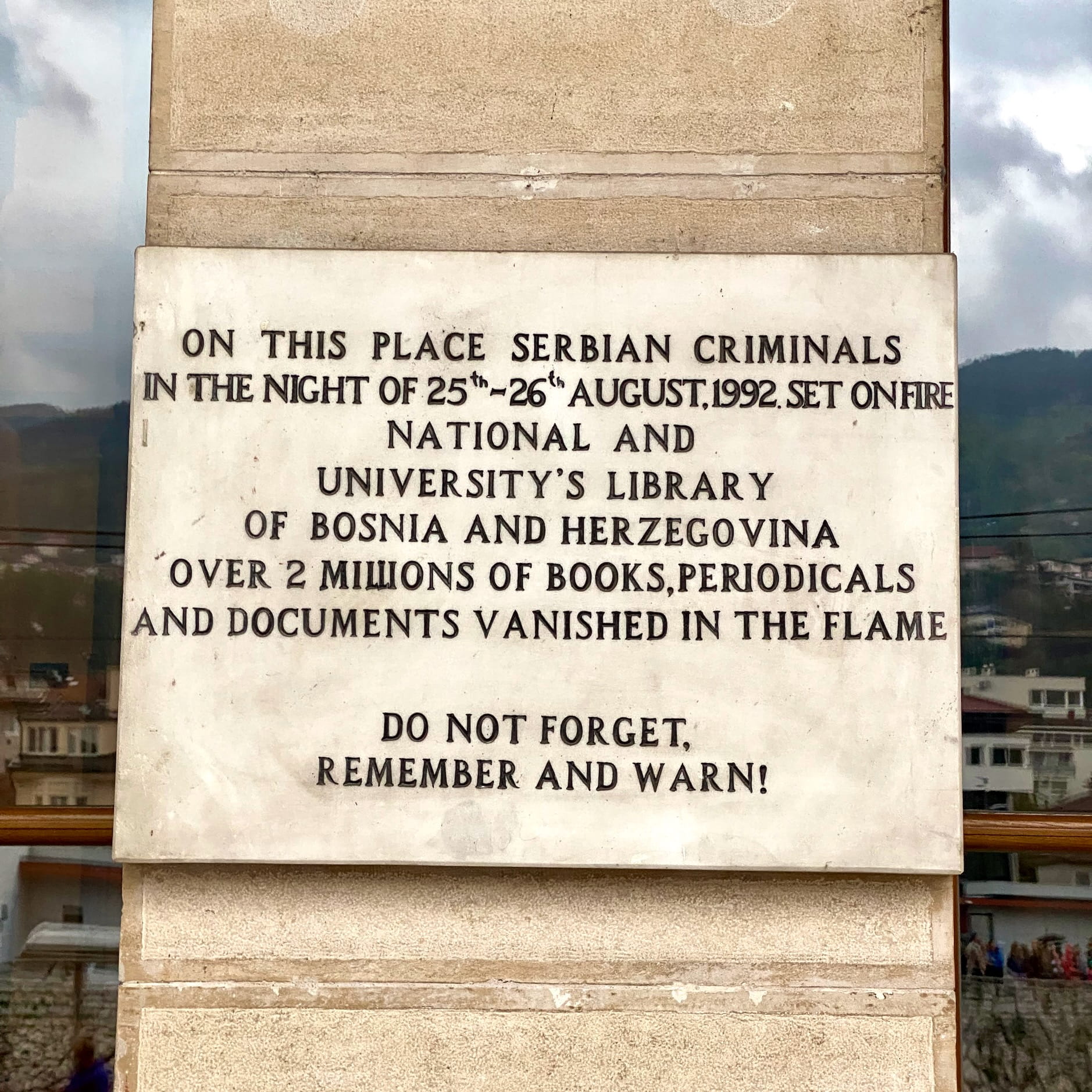

There are frequent reminders that Bosnia, despite being multicultural, isn’t a happy melting pot. In the Bosniak view, Serbs tried to ethnically cleanse the country of Bosniaks and create a Serbian state from it. These include Bosnian Serbs, as well others coming from Serbia (Yugoslavia) to join the movement.

These come in the form of signs around town:

… to museums documenting other events in the war, like this one about the Srebrenica massacre:

The wildest part to me of this whole thing is that the perpetrators of the vast majority of human rights violations, including nearly uncountable accounts of ethnic cleansing, were from the Army of Republika Srpska. I asked a tour guide, “is that the same Republika Srpska that makes up half of the country today?” She paused for a long while. “Yes.”

Now, I have to give a massive disclaimer that I spent all of my time while in Bosnia in the Bosniak state (Federation of B&H), and never went into Republika Srpska. So I haven’t heard things from their point of view. With that said, when genocide (confirmed by international courts) is involved, there is only so much you can explain with another point of view.

A Slice of Local Art

I must now perform a bizarre tonal shift and talk about completely banal things. After all, there are always plenty of ordinary sights and events and foodstuffs. This strange war↔tourism flip flopping was, for me, the hallmark of visiting Bosnia. I couldn’t square it away in my head when I was there, and I definitely can’t make sense of it in writing now, so we’re just going to roll with it.

One dark and stormy night we walked to the art museum for an exhibition’s opening. The concept was neat: he paired pieces from the permanent collection with photos he’d taken of a classic Yugoslavian bathing spot, a tiny Croatian sea town.

Didn’t understand a thing during the lecture, but there was free wine. And it was fun to see the local art community get together. Even without speaking the language, you could recognize the intimate feel of a scene before it had gotten too big.

Another challenge faced by Bosnians is brain drain. Seeking opportunities, bright yong people leave in droves for Germany.12 When a guide about our age told us this, you could feel the frustration and anguish in her voice. A college grad herself, she’d chosen to stay when all of her friends left. I wondered which I would have done in her position. I felt guilty for never having had to make this choice, and never appreciating it.

Food & Drink

You’ve heard of Salt Fat Acid Heat, but have you heard of the Balkan version: Börek Coffee Cheese Meat?

The food in the last photo was great. It was apparently a common style of eating locally, but I forget what it’s called (if it even has a special name). You go up to the counter and pick all the stuff you want on your plate kind of cafeteria-style, and just pay per plate. Great spongy bread, too. Only downside is there were no prices listed and I’m pretty sure the guy charged us at least 3x the local rate. Whatever.

Coffee is a fun ritual here (2nd photo). They’re big coffee drinkers, which I immediately liked. It’s Turkish style, bitter fine grounds steeping in the tiny metal pot with a long handle. The key differentiating factor is how you handle the addition of sweetness. Here, you take a sugar cube, dip it into your coffee, and bite directly into it, alternating sips with soggy sugar munches.

I liked that they had a process, but once the novelty wore off, I just slammed it back black.13

Ruins of 1984

Sarajevo, back when it was part of Yugoslavia in 1984, hosted the winter olympics. The bobsled track is, you guessed it, in disrepair. But it’s been so graffiti’d up it’s now a bona fide tourist attraction. They’ve modernized the cable car so you can ride it up to wander the structured rubble.

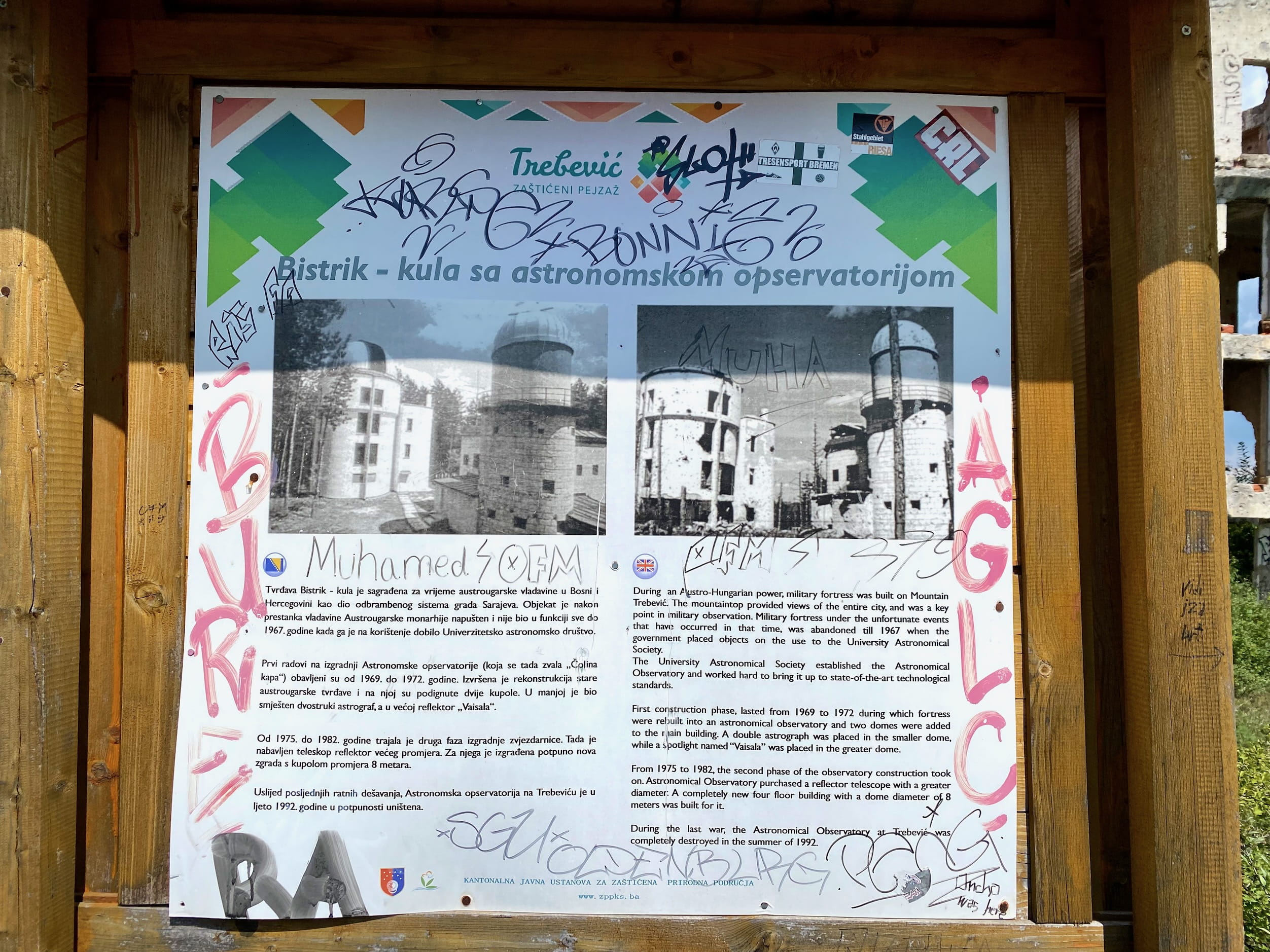

On another hill, there’s an observatory that’s like a microcosm of war’s sledgehammer to cultural development.

With that said, selfishly, if you’re into ruins like I am, it’s a fun place to check out.

μObservations14

Tesla (from a Serbian brand) making the rounds in Bosnia as well, from AC to TV to who knows what else.

Some Hitchcock-level bird terror.

Hey, if it works it works.

Anyone else like it when you can buy two different design editions of the same thing?

Every elevator was screwed up in some way. The one in the building where we stayed had two 2 buttons. Another reversed up and down. This one was in the fanciest place we went to, a two story Whole Foods-like grocer in downtown nouveau. They got pretty close.

Oh yeah, this is the store. I included this picture to describe one hobby that I’ve had since at least 2012 while traveling, which is: going into grocery stores in other places. Grocery stores are so dense and so vital to everyday life that, to me, they’re goldmines for a place’s differences. They’re packed with information. I don’t think a lot of people vibe with this, but luckily for me Julie does, so we spend a long time picking through them.

GROM

To Mostar

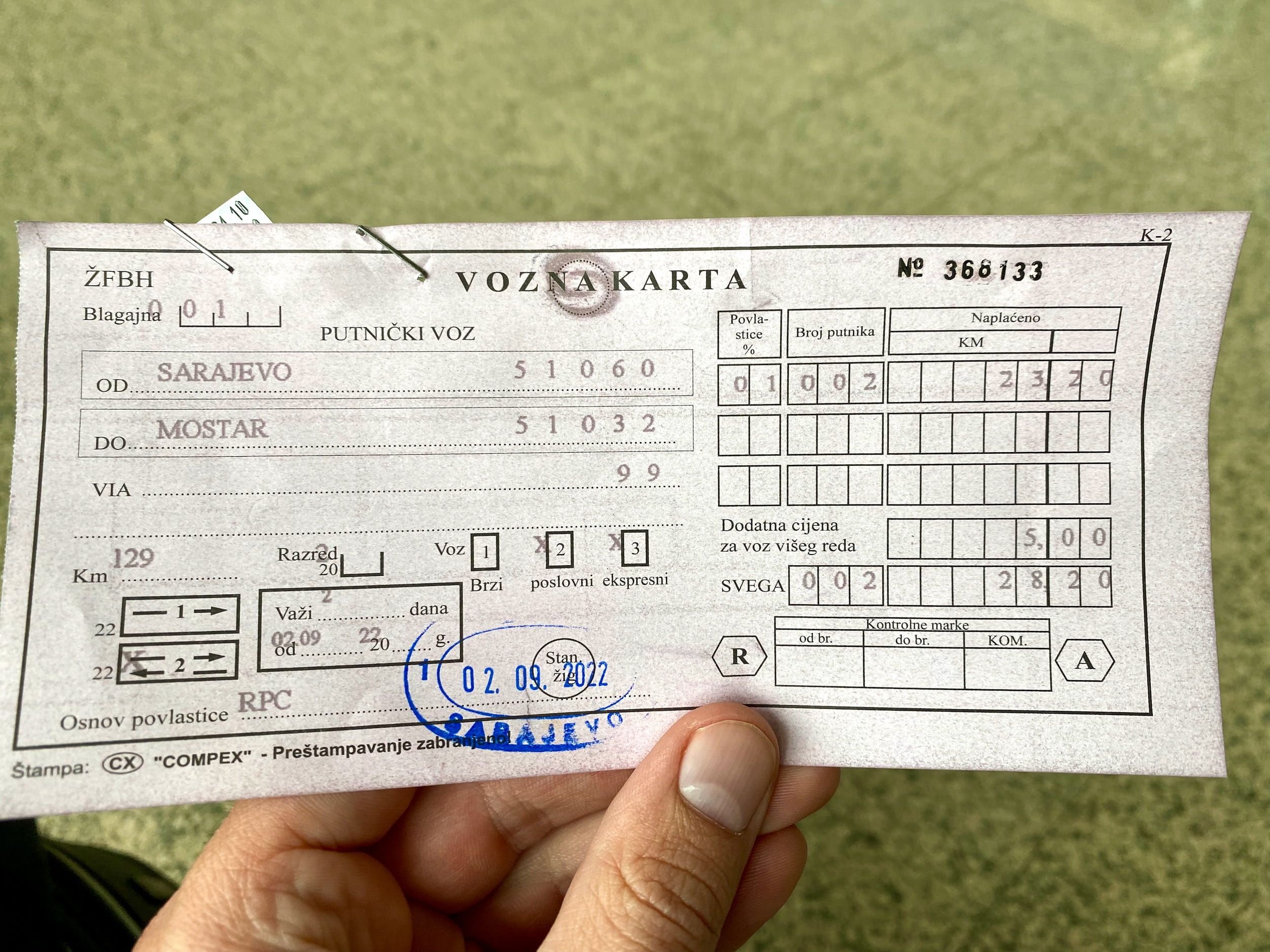

I ordered train tickets online. When I went to pick them up at the station, someone gave me this slip of paper that looked manually typewritten.15

Entering the bowels of the train station, there was just a single dimly lit hallway with no signs. I did a double take and went back out, sure I had gone somewhere wrong. Nope. One of these leads up to the tracks.

The scenery on the train ride was utterly stunning. I think it was the prettiest train ride I have ever been on, and this includes a year’s worth of taking them in Switzerland.16 What follows is a video of such obviously terrible quality that I grant you license to make fun of me for including it. But even though the glass and late day sun mangled my attempts to record the view, I couldn’t omit it, because I wanted to give an impression of just how gorgeous it was.

Mostar

We arrived in Mostar in the evening, not knowing quite what to expect. We knew it was a historic town, also involved in the war, and it felt even more remote than Sarajevo. We dropped off our bags and headed into town.

When we got there, much to our surprise, the place was illuminated by tacky colored lights and bathed in loud Eurotrance party music. We waded past stalls selling trinkets and restaurant hosts trying to lure us in.

This is such a good example of how impossible it has been for me to predict what a place will be like. I was expecting a historic tiny town with scarce tourists, wondering if anyone would speak English and whether we’d be able to find a guide to take us around the region. Instead, I found it had become kind of a cheap hangout for German retirees—who, yes, liked the blasting techno—looking to fill up on grilled meats and souvenirs.

While it’s a bit disappointing to find yourself in another cobblestone Disneyland, it does make life easier. I was able to book a full day tour at 10pm for 8am the next day.17

Anyway, before I get to that, let’s look at Mostar a bit.

Famous bridge. Around for hundreds of years before, you guess it, it was destroyed in the war. People jump off of it and dive into the water for tips, and for competitions. This is apparently quite difficult and dangerous. Back injuries, etc.

Shell blasts, bullet holes, and building ruins sit alongside tourist entertainment attractions. The historical immediacy of the surroundings keeps the past on your mind.

It felt increasingly bizarre to come as a tourist, but it’s hard to describe why. It’s not that ruins or bullet holes made me uncomfortable. Instead, it somehow seemed inappropriate to be indulging in fun activities, to be cooked for and served food, all fueled by my home country’s relative stability, strong currency, economy, military, and good passport. Spreading money is good, of course, but I couldn’t shake a feeling that the world had gotten things backwards. That after enduring a war, people should catch a break.

Bosniak general who led a big charge out of Mostar at the end of a grueling siege to connect it to Bosnian military territory and establish a supply line (IIRC). Both sides of the old war still have odes to their military heroes around on walls.

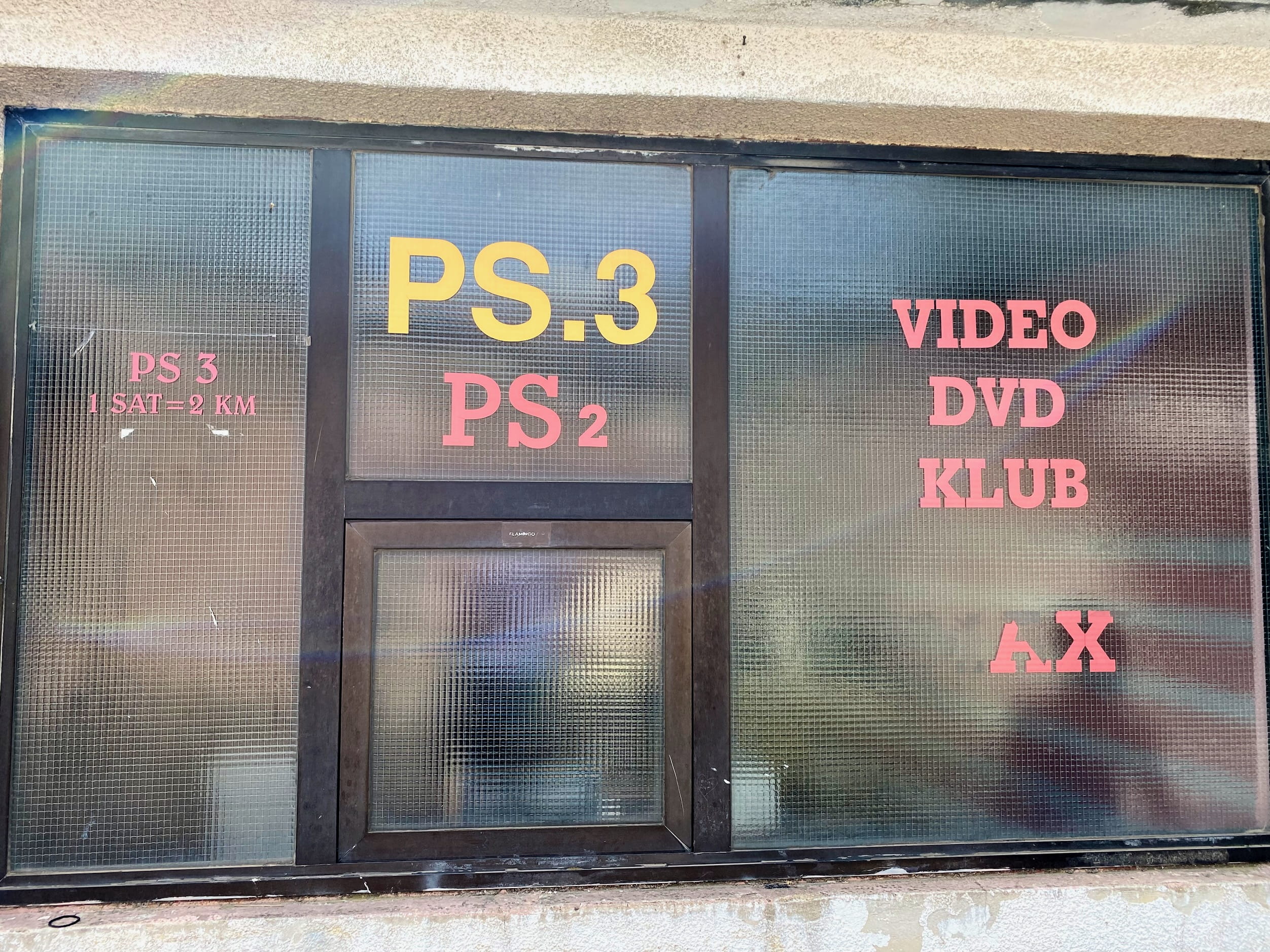

Rental store. Maybe.

This immediate juxtaposition of war remnants and modern tourism would be a theme for our tour of Herzegovina as well.

Herzegovina

The region in the south end of B&H, Herzegovina is a pretty place. It reminded me of Greece, with shrub-dotted hills and towering cyprus trees. The rocky landscape held a restrained lushness. Ripe just around us was:

- Olives

- Apples

- Cherries

- Figs

- Walnuts

- Kiwis

- Grapes

- Pomegranates

We took a full day tour. Our guide was a Bosniak Muslim whose family was in the war. We got to hear stories of his family’s experience.

One thing that I immediately noticed is here, the stories were all Bosniaks vs Croats.18 The siege of Mostar, the internment camps—this was all Croatian forces. In Sarajevo, the focus was on Serbs (e.g., Siege of Sarajevo, Srebrenica massacre).

Blagaj

A village with a famous Islamic monastery.19 We learned that Bosnia is a major destination for Middle Eastern tourists. And while Bosniaks are predominantly Muslims, they didn’t fit my preconcieved notion of what Muslims look like. E.g., our guide had blond hair, and he told us most Bosniak Muslim women don’t wear hijabs. So the many hijab-wearing women we’d see in town are largely tourists from other Islamic countries.

One of the cooler features of the site was that, at a certain spot, the river came up to a rocky bank, and then poured out from under it. I’d never seen anything quite like it.

Bunski Kanal

We continued on to an area that sounded boring on paper but was actually pretty neat to see. It’s a place where two rivers join, with a shrubby marshland connecting the banks where one spills over into the other.

Different algae and amounts of sun make them different colors. (Can’t really see that here, sorry.) Our guide told us that despite being narrow, they reach 14 meters (46 feet) deep!

As we were walking around, Julie came across an ammunition shell. They are still easy to find.

Počitelj

We came to a fortress town called Počitelj. It had been ethnically cleansed and abandoned during the war. The government tried to get people to come back, but a Croatian internment camp had been on the hill across from town. The former residents couldn’t stomach the sight. So it remained a ghost town. Only a handful of vendors hung out in the streets, selling juice and trinkets to tourists like us on their way through.

Way off in the distance, you could see a huge overpass construction project partway through. (Was it progressing, I wondered?)

On the road, we’d hear stories of our guide’s mom and dad’s experience in Croatian concentration camps. They both survived, but had been split up during the war, his mom with two toddlers, and his dad alone in another camp. I won’t go into the horrific details, but human accounts of war like this do a damn good job of making the violent territory struggles of rulers seem utterly pathetic and shallow. The magnitude of human suffering inflicted is totally lost in statistics. It was awful hearing about a single family, and the war killed over a hundred thousand, and made millions abandon their homes.

Kravica Waterfalls

We spent hours hearing about the war and the history of the local people and places. The mood was decidedly somber. Then, as per tour guidelines, our next stop was a swim at the famous Kravica Waterfalls.

While quite strange tonally, I had to admit it was a beautiful spot for a break.

We finished our tour back at Mostar, learning about the (second) siege where the city was split in two down the river. Our guide also recounted a couple of his own firsthand post-war experiences. Fights broke out as tensions remained high between the ethnic groups. The town had been split down a street to divide Croats and Bosniaks. He and his friends—Bosniaks about ten years old—were scared of ever crossing the street into Croat turf.

Today, though, he and his family live in the Croat part of town. He said they chose this intentionally, one gesture to lead by example and try to overcome the divisions of the past.

On Our Way

Mostar’s train station made Sarajevo’s look nearly normal in comparison. The entire main floor of the station was closed up and locked off, all the stalls and offices collecting years of branches, dust, and graffiti. You could still see into it by climbing up a dead-end stairway.

The functional part of the station was just a small downstairs area. As we waited, some girls by us set up their rugs for an evening prayer. Julie, still destroyed by the worst food poisoning we’d get this year,20 requested I go outside to eat my evening börek, to abate the smell of warm cheese and greasy dough. There was nowhere left to sit, so I ate standing up.

After a night back in Sarajevo, the driver who dropped us off at the airport said “good luck.” I hoped this was just a funny English moment, but part of me felt like he knew what experiences the airport would bring. We did have one hell of a commute after this.

Footnotes

Bosnia having a tiny bit of coast on the Mediterranean is an interesting factoid on itself. Because Croatia extends before and after it on the coast, you used to have to drive through Bosnia if you wanted to drive down the length of Croatia. You’d have to go through border control, get your passport stamped and everything, just to make it through that tiny stretch of highway, and then go back through Croatian border control. (That Dane I mentioned in the Serbia post said he’d gone to Bosnia, and when I asked about his experience—because we were headed there next—he sheepishly admitted they had actually just gone through this road segment on the way down Croatia.) Croatia was tired of this, and they very recently (like, July 2022) finished building a massive bridge off the coast, connecting the Croatian mainland to a Croatian peninsula, to avoid having to go through Bosnia. Sounds great, right? Less hassle for everyone? Well, there’s drama to this as well. Though it’s an enormous bridge, it’s not high enough for shipping vessels to get under it. This isn’t a problem now, because Bosnia’s tiny cost town Neum doesn’t have any kind of harbor, much less one that could process gigantic boats. But, it does prevent Bosnia from ever having a shipping port in the future. Would they ever make one? Croatia argued not, and that building the enormous bridge high enough to accommodate that possibility wasn’t worth the wild budget inflation that would have entailed. And here we are. ↩︎

Slavic is not a language, and is a simplification here. The language is Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian, which is a single South Slavic language. Each of those components in the name (e.g., Bosnian) are mutually intelligible standard varieties of the language. Here’s the Wikipedia article if you’re curious for more. ↩︎

Technically the two divisions of Bosnia are caled entities, not states. I try to use wrong but relatable terminology whenever I can. ↩︎

Technical term for super president = chairperson. The three presidents thing has interesting drama, too. The Federation of B&H is mostly Bosniaks—there are actually very few Croats there, even though they get a whole president. And technically, when you’re in the Federation of B&H, you pick which president you’re voting for. See where this is going yet? So last election, Bosniaks came up with a scheme to split their votes so they could elect a Bosniak for the Bosniak president slot, and a Bosniak for the Croat president slot. And it worked. ↩︎

Here’s an example re: political deadlock. One guide told us that a central component of the government (I can’t remember which) has twenty-seven representatives, nine each from the three ethnic groups (Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian). Any ethnic group can decide to veto something, and it’s dead in the water; even 18 vs 9 can’t break through. As a result you get, e.g., Serbs protecting Serbian and Russian (and Chinese) interests: stopping progress to join NATO, preventing sanctions vs Russia, that kind of thing. ↩︎

Macedonia is Now called North Macedonia because Greece didn’t like that name. That argument took 28 years. ↩︎

This stuff gets even more complicated because back then, Serbia wasn’t Serbia, it was just all that was left of Yugoslavia. (It was like Serbia plus Montenegro, but basically Serbia power-wise. Also Kosovo didn’t exist yet.) So, technically Yugoslavia was backing the Serbs in Bosnia. This has side effects like the Yugoslavia army being the “JNA” because you write “Yugo” with a “J” instead of a “Y” in Slavic languages, so by the time you’re reading “JNA” and not “Serbian military” you can get quite confused by the whole thing. See what I mean about the fractal? ↩︎

In Mostar there is one school on the Croat/Bosniak dividing line. Though kids of both ethnicities do go there, they attend classes at different times of the day so that they don’t mix. ↩︎

Here nationalism is a dividing force—Serbs supporting Serbia, and Croats supporting Croatia. These stances are reinforced both by those countries as well as local politicians. ↩︎

Eagle eyed readers might notice the Bosnian War ended in '95, but the Siege of Sarajevo ended in '96. What gives? Well, Serb controlled neighborhoods kept firing missiles into town for a couple months. ↩︎

People told me the USA used to be a big immigration destination for Bosnians, but it became much harder after 9/11. Why, I asked? They said it was because they are Muslim. ↩︎

I learned to drink coffee in 2012 by drinking straight espresso. It was a DIY situation and I was too unskilled to make lattes. And nobody told me you could stir sugar in. My palette has sought raw bitterness ever since. In hindsight, this was definitely a gateway drug to IPAs. ↩︎

The μ is supposed to stand for “micro.” I know, I know, sorry. ↩︎

I’m almost certain I’ve never used the word “typewritten” before. I thought it’d be “typewritered.” ↩︎

Granted, I spent a lot of my time on Swiss trains drinking beer and trying to fit in, so maybe some were prettier. Look, whatever, it was nice, OK. ↩︎

I do feel guilty about this—making someone get called into work with barely a night’s sleep of notice. I apologized to our guide about this, and he was probably just being nice, but he said, hey, it’s just part of the job. ↩︎

Again, all details here are fractal like, making it hard to say anything simple. E.g., the Siege of Mostar actually kind of happened twice, first with Serbs (Yugoslavia) fought back by Croatians, and then later on, with Bosniaks vs Croats. Most of what we heard about was the second time, when humanitarian aid was cut off. ↩︎

I was spared this time. We think it might have been the sole piece of sad lettuce from her dinner. It was a rough night. ↩︎